Wool to Sweater in 70 Steps

I couldn't find all 70 steps, but a lot more than roaming sheep and knitting goes into making a sweater.

Almanacs are resources to understand how natural cycles interact with specific topics. Each month, The Mindful Designer’s Almanac offers musings about natural fibers harvested that month or season. In January, shepherds in New Zealand shear their sheep.

During the Southern Hemisphere’s summer, shepherds in New Zealand shear their sheep. Some of the wool goes to the few remaining mills in New Zealand to transform into yarn and finished goods. 80% of New Zealand’s raw wool is exported, primarily to China, India, and Italy.

Once it leaves pasture, wool is the most processed natural fiber. I recently read that wool can undergo over 70 processes from raw fleece to finished goods. I decided to investigate the steps from sheep to garment for 100% wool garments and see how many steps I could find.

Note: clothing production is complex and usually lacks transparency. It is impossible to fully understand what processes go into the clothing we wear. In most cases, especially when the processes have negative effects, brands disclose the bare minimum: fiber content and country of origin. For example, a t-shirt labeled 100% Merino wool and made in Vietnam. However, the shirt is 20% synthetic coatings, dyes, and finishers by weight and the merino wool came from sheep in New Zealand, then went to China for fabric production, and then sent to Vietnam for sewing.

Location 1: Farm

Step 1: Grow Wool

All wool starts with sheep, which grow a fibrous fleece to protect themselves from the elements.

Step 2: Shear sheep

During the warmest months of the year, shepherds shear their sheep to help the sheep stay cool, prevent parasites and disease, and sell the fleece.

Location 2: Tops Factory

Once it leaves the farm, wool fleece usually goes through a system of wool buyers and brokers, who sell it to a tops (wool tops are semi-processed wool fiber) facility.

Note: There are two types of wool yarn, worsted and woolen, and each has its own process. Worsted is used for longer staple wool fiber and woolen is for shorter staple fiber.

Step 1: Scouring

Raw wool fleece is known as greasy wool because it contains oil called lanolin. It also contains dirt, branches, leaves, and whatever else the sheep picked up while roaming. Scouring is a series of baths with detergents and alkalis to clean the wool and remove lanolin (which is sold to the cosmetic industry).

Step 2: Drying

Machines dry and beat the wool to remove any leftover sand and dust. Then the wool goes to a closed room or bin until its moisture level reaches an equilibrium.

Step 3: Carbonizing (optional for the woolen process)

Carbonizing is the process of soaking wool in sulfuric acid, which breaks down cellulose (dried leaves, sticks, etc.) into easy-to-remove carbon and water.

Step 4: Carding (woolen process)

The scoured wool is typically coated with a synthetic lubricant and water to reduce friction and static. The lubricated wool goes through a series of rollers covered in pins to detangle, straighten, remove containments, and create a homogenous web of fiber.

Step 5: Gilling (worsted process)

Gilling machines are rollers with large combs that straighten and position the fibers to reduce breakage during spinning.

Step 6: Combing (worsted process)

A combing machine further straightens and aligns the longer fiber while removing vegetable matter and shorter fibers. The result is a continuous fluffy sliver of wool.

Step 7: Superwash

Wool fiber is covered in scales that intertwine and bring the fiber closer together in warm water or with a lot of agitation (i.e. normal machine washing). Superwash wool is a process that uses a chlorine solution to erode the scales and coats the fiber in a polymer resin to hold down the scales, making wool machine washable.

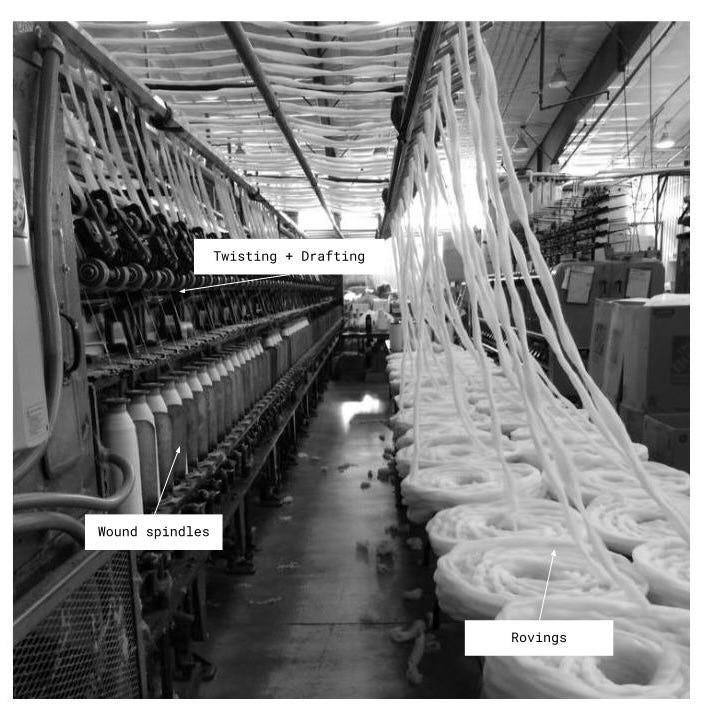

Location 3: Spinning mill

The clean and homogenous wool goes to a spinning mill where it is pulled and twisted into yarn. The spinning process differs based on the characteristics of the input, fiber length, woolen or worsted, and fiber strength, and the output, desired yarn count (yarn thickness), yarn structure, twist level, and yarn strength.

Step 1: Drawing

A roving machine uses small rollers to compress, pull, and slightly twist the wool into a roving.

Step 2: Drafting

The fiber in a roving is still loose and easy to pull the individual fibers apart. Drafting is a pre-spinning step that uses tension pulls and thins the roving into a denser, uniform line.

Step 3: Twisting

The drafted fiber is twisted a predetermined amount of times, based on the desired yarn output.

Step 4: Winding

The twisted fiber winds around a bobbin. Industrial winding machines have a sensor that checks for and removes any slubs or inconsistencies in yarn thickness.

Step 5: Repeat

The fiber continues through the process of drafting, twisting, and winding until it reaches its desired twist, strength, thickness, and structure.

Step 6: Plying

Some wool yarns are plied, meaning two or more of the finished yarns are twisted together and rewound onto a bobbin.

Step 7: Waxing

To reduce the friction of the yarn for knitting and weaving machines, wool yarns are coated in a synthetic wax that contains paraffins, oils, and emulsifiers.

Step 9: Dyeing

The dyeing process can happen when the wool is in fiber, yarn, fabric, or garment form. The vast majority of wool dyes are synthetic mixtures derived from oil. Some wool is dyed with natural dyes and some wool colors come from the natural color variation of sheep.

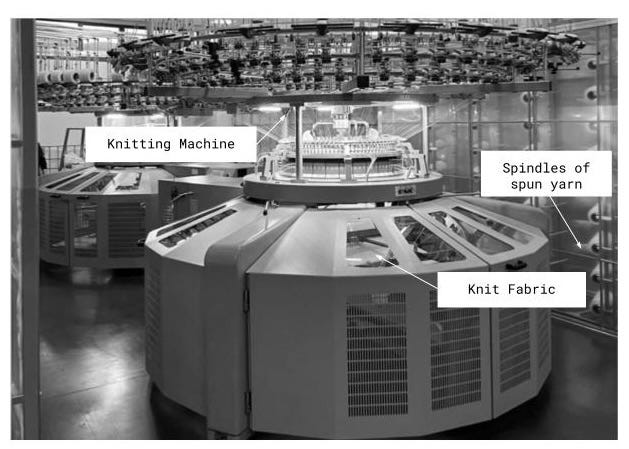

Location 4: Knitting or Weaving mill

At weaving mills, the wool yarn overlaps and interlaces to create fabric. At a knitting mill, machines tie the yarn into a series of knots to create fabric or knitted garments.

Step 1: Knit or Weave

At this stage, there are almost infinite possibilities as to what the yarn can become. Circular knitting, flatbed knitting, hand knitting, machine knitting, handloom knitting, power woven loom, handloom, and twill loom are just a few techniques that transform wool yarn into fabric or garments.

Step 2: Scour/ Wash

Once finished, the fabric or garment goes through a final wash. The wash removes any water-soluble lubricants and oils added throughout the process. The final wash is an opportunity to make any final changes to the hand (feel) and characteristics of the wool. For example, softeners chemically break down the fabric to give it that worn-in feel, napping agents break up loops made in knitting to create fuzzy terries, and chemical coatings cover the wool with anti-microbial, anti-odor, UV-resistant, fire retardants, water-repellents, etc.

Location 4: Cut and Sew

Full-fashion knitting transforms yarn into finished garments without the need for cut and sew. Knitted and woven wool fabrics need to be cut and sewn to transform into garments.

Step 1: Cut

A predetermined pattern has the 2d dimensions of a design. The pattern is cut out of the fabric into various pieces.

Step 2: Sew

The process of sewing together the pattern pieces to make a 3d garment.

I didn't get close to finding all 70 steps. I’m sure I missed a few, and many of the above steps are made up of smaller steps. Even with the steps I did find, the journey from the sheep to the garment is highly labor and chemical-intensive. I imagine the wool that goes through the 70 steps would result in material drastically different in structure and functionality from the raw wool.

When raw wool fiber sheds off the animal, it naturally breaks down within a few weeks and composts back into the soil as organic matter. Some processing has to occur to preserve the fiber’s integrity long enough to make a garment functional. With the current industrial base, there is constant innovation around mechanically and chemically altering wool in the pursuit of creating more functional garments. But, at what point is the pursuit redundant and based on the assumption that doing more is better?

There is a line where over-processing causes natural fibers to become composites. A line where you begin to lose the naturally beneficial functions of the fiber. For example, adding synthetic UV coating because the synthetic processing used diminished the wool’s natural UV absorption. In this case, more is not better, especially when you are replacing properties that sheep have been perfecting over millennia with innovations less than a few decades old. The real innovation would be finding ways to reduce the steps to minimally process wool and preserve its natural benefits.

My brand, Mairin, offers low-intervention wool garments. I work closely with my suppliers to reduce redundant processes and avoid synthetic chemical inputs. You can shop here.

Notes

https://oklahoma.agclassroom.org/resources_facts/agfacts_sheep/

https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/wool

https://www.woolmark.com/industry/product-development/wool-processing/worsted-scouring/

https://www.woolmark.com/industry/product-development/wool-processing/woollen-spinning/

https://www.woolmark.com/industry/product-development/wool-processing/worsted-spinning/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780323995986000050#:~:text=The%20blending%20of%20wool%20with,other%20materials%20is%20also%20studied.

Conversation with Beth Pollack, Safety Products Manager, Draper Knitting

This newsletter is so interesting and well-documented. I have a complicated relationship with wool, as I genuinely value wool's natural properties for daily life and outdoor activities, and I love a nicely made Merino long-sleeve. However, I'm concerned about brutal practices like mulesing inflicted on sheep, and I'm worried about the environmental impact of animal agriculture. I have been traveling in New Zealand for 3 months, and the amount of rural land accommodating grazing sheep and cattle is impressive; it's estimated that 85% of New Zealand's native forests are gone due to animal farming and other agricultural activities. At the end of the day, I stick to the principle that certain things are still good in moderation. And that's why I like your brand; your practice is rooted in transparency and intentionality, with a small selection of wonderful timeless pieces, not hundreds of different styles. I'm excited to see what's next and grab a piece or two when I'll need them :)

I love this article, I had never read something so detailed about wool processing. Truly eye opening!