Welcome to a new Mindful Designer’s Almanac series that explores my sourcing, design, and development decisions for my clothing brand, Mairin. I put a lot of thought into each piece I release and think this is the perfect place to explain how I design, meet the people who make them, and source the materials for them.

This week, I released my first sweater! It’s a hand-knit, rolled neck sweater made with 100% Andean Highland Wool in Peru. It is based on a beloved sweater my mom knit me a few years ago.

THE DESIGN

Last year I went to Peru to help my friend Bridget, the founder of Zii Ropa, develop a knitwear collection and check on a freelance project I had been working on based in Cusco. I had just started developing samples for my brand and figured I might as well bring my favorite sweater down to replicate.

In my early twenties, my mom got really into knitting, and I was lucky enough to get a handful of sweaters. I would send her design inspiration, go to the local yarn store with her, and a few months later, she’d give me my new custom sweater. My favorite is a 100% Montana-grown wool sweater. It has raglan sleeves and a rolled neck and hem. It's slightly snug and cropped, as if you accidentally washed one of those ‘90s, oversized J. crew roll-neck sweaters. It has been my go-to sweater for eight years. I have worn it well over 1,000 times. Even when I wear other sweaters, I usually have this one under it. It's the perfect mid-layer for any activity.

THE KNITTERS

In Peru, Bridget and I met with my friend Carolina who runs a knitwear production company in Lima called Revolution Knits. She and I met a few years earlier when I was in Peru developing a sweater supply chain for Christy Dawn. The knitters she works with, her quality standards, ethics, and commitment to sustainability are by far the best in Peru. She produces sweaters for only a handful of brands, all known for their quality. We met by happenstance on my first trip to Peru back in 2021.

Long story short, my first trip to Peru did not go as planned. Among other unlucky circumstances, I met an alpaca farming project and a handful of knitters that did not quite meet our ethical or environmental standards. In a last-ditch effort to find a like-minded partner, I went to a natural dye studio on my second to last day there. The artisan lived a few hours up the coast from Lima in a sprawling house surrounded by huge vats of dyes, tables full of dried flowers and bark, and rows of drying skeins of yarns. She was a very quirky, mad scientist-type and seemed to dislike the knitters I had met with earlier in the trip just as much as I did. On my way out, I asked her who she preferred working with and she gave me Carolina’s number. I was so relieved by Carolina’s professionalism and respect for the knitters she worked with when we chatted in her studio the next day.

I have been collaborating with Carolina ever since. The freelance work that partially brought me to Peru last fall was helping her build a small-scale, traceable alpaca supply chain. Carolina partnered with the NGO Innovar y Compartir, which works with alpaqueros to regenerate their pastures using traditional and new land management techniques. Carolina buys their fiber at a fair price. She then works with a small spinning mill and her partner knitters to transform them into sweaters. It’s a sweet project and I’m planning a sweater using this yarn for next fall (Wol Hide is releasing sweaters from it this year).

Last fall at Revolution Knit’s studio in the Barranco neighborhood of Lima, Carolina and I fit the sweater my mom made. The armholes were tight, so we lowered them an inch. The body and sleeve lengths were too cropped, so we added to each. Other than those changes, I wanted a perfect replica of my sweater, including hand-knitting it. The first thing I learned when I started working in knitwear was that hand-knit sweaters are simply better than machine or hand-loomed ones. Hand-knitting adds texture, loftiness, and that handmade feel you can’t quite put a finger on. It’s also significantly more expensive for obvious reasons, especially with Revolution Knits, which ensures all its partners earn a fair wage.

Revolution Knits works with a talented network of hand-knitters on the outskirts of Lima. The network is centered around the head-knitter, she is the first one to get a design and translates it into a sweater. Then she WhatsApps with her knitters, the ones available come to her house, learn the design, take home a few bags of yarn, and knit. If they have any questions they go back to the head-knitter for help. I’ve spent a couple of afternoons at a head knitter’s house. We sat around gossiping or problem-solving, all while they knitted at a rapid clip. My sweater design is fairly simple, so it takes them around two to three days to knit each sweater.

THE MATERIALS

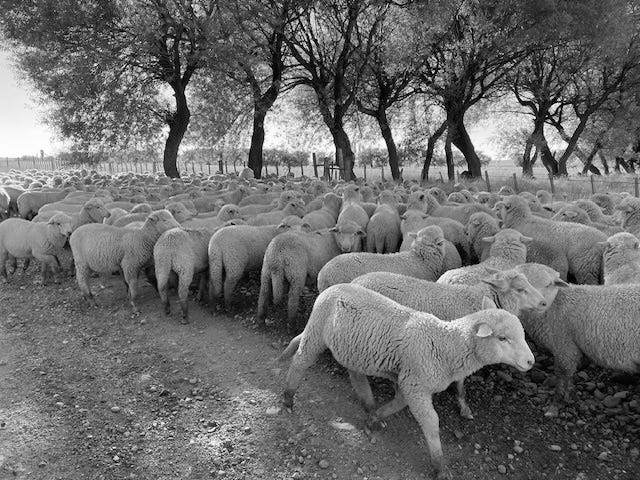

A replica of a wool sweater should be made with wool. As a small brand, I’m limited to stock yarns, so I don’t have to invest in a huge order. Incatops, one of the main yarn suppliers in Peru, has around 20 stock yarns every year. One of its stock wool offerings is called High Andean Wool. It’s a fine wool, slightly less fine than merino, that comes from ranches in Argentina. It’s soft, sturdy, chunky, and perfect for this sweater.

High Andean Wool comes in five undyed shades. Sheep are naturally many shades of creams, browns, and grays. A majority of sheep for wool have been bred to be white because it is easier to mass produce and overdye, but the diversity in color remains in a few flocks. At the mills that clean the fleece, a group of women hand-sort the fiber into general categories: natural, light browns, dark browns, light greys, and dark greys. I chose light and dark grey. Although I ended up with sweaters in two general, grey tones, each sweater’s color is a unique reflection of the sheep.

The natural color variation is the most interesting thing about these sweaters to me. It means I can offer color options without using synthetic dyes. The yarn also avoids chemical treatments because it is not super washed- the chemical and mechanical process that removes wool’s hairiness (what causes pilling, but also what makes wool so insulating). The less I process the raw material and interfere with the natural fiber, the better I can preserve the fiber’s natural benefits.

Wool's purpose is to respond to the outside environment to keep sheep warm, dry, and comfortable. Most of Argentina’s wool comes from Patagonia where the low temperatures, high winds, and dryness make grazing sheep one of the only agriculture options. These sheep roam in valleys close to the Arctic with huge glacial peaks towering around them. The resulting wool is extremely efficient at keeping you warm in the cold.

Knowing where my raw materials come from allows me to make more informed design decisions. Wool from near the Arctic is perfect for a sweater whose main function is to keep you warm. You can always take a sweater off, as opposed to a baselayer, which needs to be more dynamic. For my baselayers, I use wool from Oregon, Colorado, and California- landscapes that experience cold winters and hot summers.

The only downside of this wool is its lack of specific traceability to the farm. Although many ranchers in Argentina are embracing holistic practices that preserve their pastures, Argentina’s landscapes are getting overgrazed in places. I have been looking into options for tracing to specific ranches in Argentina, but I need to grow my brand before I can really explore and invest in them.

THE PRICE

Part of me wants to justify the price of the sweater by saying, “Sweaters are expensive to make”, but I hate when brands say that kind of thing. They aren’t expensive, they’re also not cheap, they cost what they cost. This specific sweater costs what it costs to buy the fleece from ranches in Argentina, transport the fleece to the mill, hand-sort the color variations, clean the fiber, transport the cleaned fiber (called tops) from Argentina to Arequipa, spin the tops into yarn, transport the yarn to Lima, hand-knit the sweater (2-3 days/sweater), inspect and pack the sweater, and transport it to my studio in Montana. Then I add what I think is a reasonable profit and voila, you get $325. If you, like me, wear this sweater 1,000 times, that’s 32 cents per wear. If you don’t think you will wear this sweater 1,000 times, you probably don’t need it.

Alright, those are all the details that went into my sweater. If you got this far, thank you, comment to let me know if you enjoyed this, and buy the sweater. :)

I am new to the newsletter and can’t say enough good things about this! Interesting, illuminating, transparent; we should all know more about where our clothes from, to say the least. ❤️❤️❤️

I love your encouragement to buy something you will love and wear a 1000 times. That would solve a lot of our waste problems. How about smaller closets, filled with loved and frequently used things?