Welcome to a new Mindful Designer’s Almanac series that explores my sourcing, design, and development decisions for my clothing brand, Mairin. I put a lot of thought into each piece I release and think this is the perfect place to explain how I design, meet the people who make them, and source the materials for them.

I bought a pair of nylon, pull-on hiking shorts at the end of high school. They soon became one of my favorite pieces of clothing and my go-to shorts. Seven years and thousands of wears later, I lost them during a move. I bought a replacement, but the company changed the fabric, fit, and sewing. The new pair didn’t do as great a job of masking what it really was: about half a pound of plastic in shorts form. While the first pair felt like cotton, the replacement felt like the water bottles they were made from. They also didn’t nail the fit. The first pair was snug enough to make me feel covered but loose enough for movement, they were short but not too short, they had sewn-in pockets, and all the seams were clean.

When I first started developing my brand, I knew I wanted to recreate the best shorts I ever owned. It took over a year and a half to develop and produce them. The shorts are finally here!

THE COTTON

In November of 2023, I invested in growing the cotton for the shorts. Oshadi Collective is a small vertically integrated textile company in southern India. They have a group of about 200 cotton farmers who grow cotton on their small farms using traditional and regenerative practices. They grow a native cotton variety called Surabhi cotton with no synthetic inputs. Oshadi uses a community-supported agriculture model, so brands invest in a certain number of acres. The investment pays for all costs, including farmers’ wages, of growing cotton regeneratively. At the end of the season, the brand receives all the cotton from that acreage. I invested in the smallest amount of land they offered and waited for the cotton to grow.

I originally met Oshadi Collective when I was working with Christy Dawn. You can read about that here.

THE FABRIC

While they grew the cotton, I started developing the style. I made a few pairs of shorts using cotton from my mom’s fabric store. I figured out a fit I liked, but the fabric, a cotton poplin, was too stiff. I wanted something with more drape and durability. On a visit to LA, I stopped by a fabric store and found a roll of the perfect deadstock cotton. It was made of a fine yarn, densely woven. It was soft and drapey, but held its shape. I made a sample of the shorts using some of the yardage I bought and sent a yard to Oshadi to replicate.

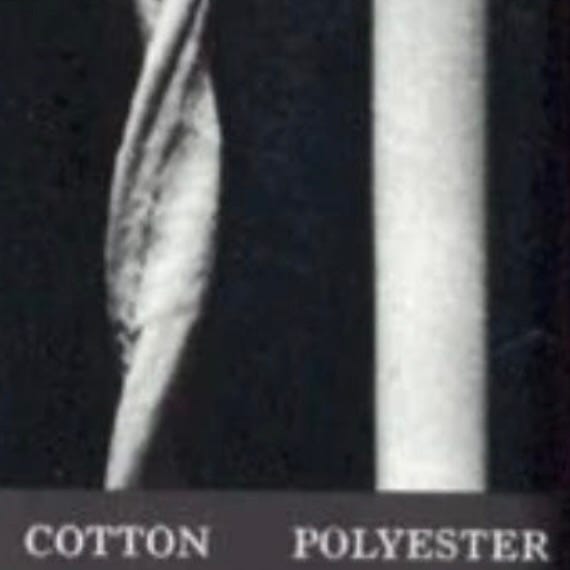

The Surabhi cotton from Oshadi’s farms is perfect for this kind of fabric. It is a long-staple cotton that can be spun into super fine yarn, then made into a tightly woven fabric. My friends who’ve tried the shorts and pants ask if it’s a blend. It’s not. It’s 100% cotton. It feels like a blend because most blends mimic the feel of natural fibers, especially expensive natural fibers. I used an expensive cotton (i.e., fine cotton), spun it into a thin yarn, and wove it tightly (i.e., using a lot of expensive yarn). The result is a relatively pricey yet super durable fabric. Instead, I could’ve used petrochemicals to create a thin yarn and densely weave it, which is a much cheaper option. Typically, fine yarn is exclusively used for lightweight or less dense fabric, like gauzes, lawns, and voiles. There are some exceptions, like heavier poplins, but these are mostly used for garments with higher perceived value, like dress shirts, not casual hiking shorts.

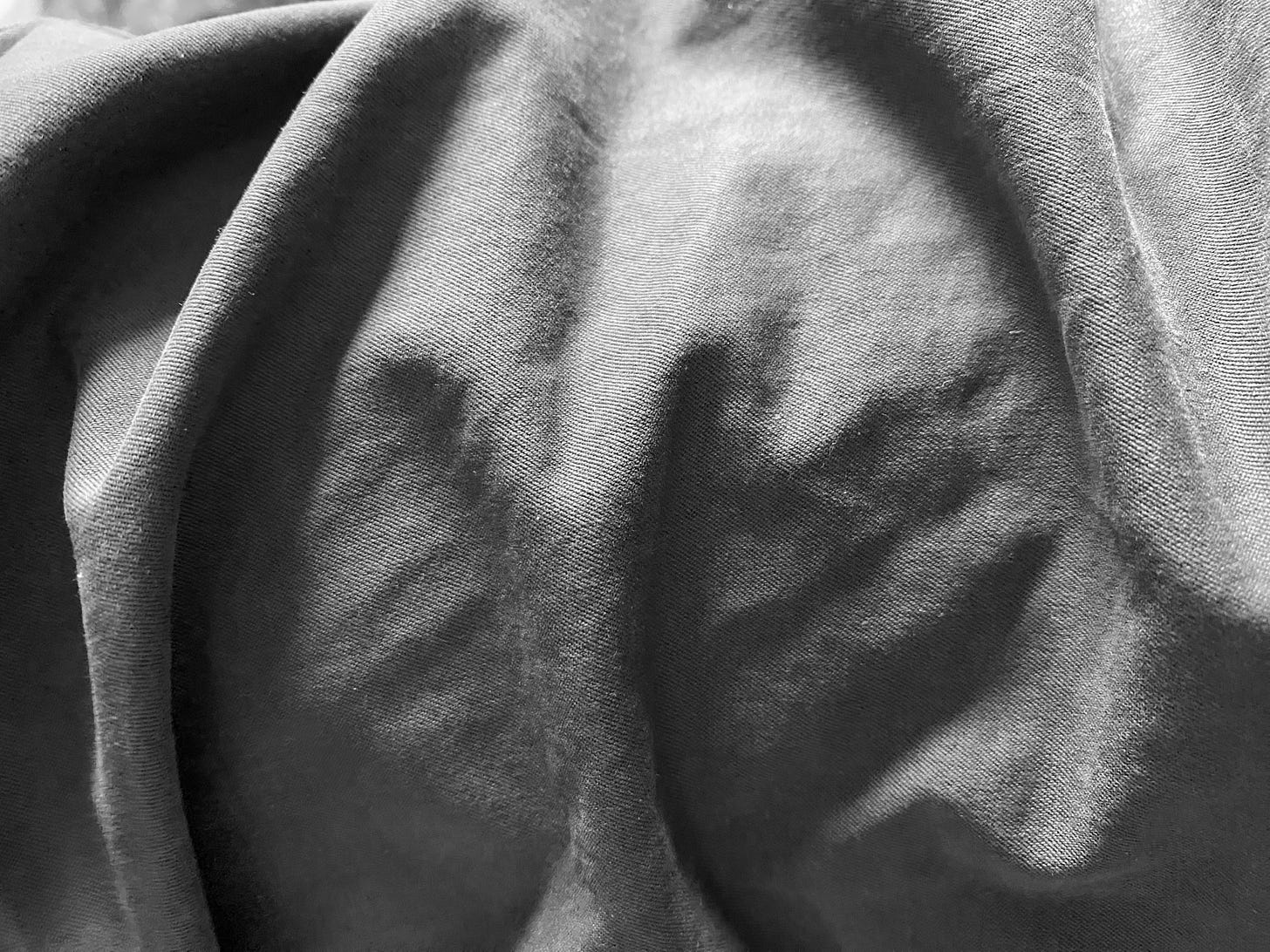

The finished fabric went to an artisan who extracted minerals from the soil and used them to dye the fabric. The dark gray comes from a mineral called umber, a naturally rust-colored mineral. The artisan burns the umber to get the darker, grey tone. Mineral dyes are more colorfast than plant-based natural dyes and do not contain any synthetic chemicals. The shorts come in two colors– slate dyed with burnt umber and natural undyed.

THE CONSTRUCTION

When I first learned how to sew clothing, the tailor who worked at my mom’s store would help me. She taught me the most important thing about a garment is that the inside should look as good as the outside. The better the inside looks, the longer the clothing will last and the better it will feel on. For the shorts, I chose to use flat-felled seams– a reinforced seam where the raw edge is enclosed inside of it. The more common overlock seam is when the raw edge is exposed but stitched to prevent fraying. Flat-felled seams are slower to sew and take more skill, but they are much prettier and more durable than the alternatives. Like using fine cotton to make heavier fabric, flat-felled is usually exclusively used for tailoring or higher-end products.

THE CARE

Technically, you can machine wash and dry your shorts. I would recommend washing them with similar colors and in cold if you choose that route. You can also hand-wash in cold and hang dry per the label. The latter will cause the least wear and tear on the garment, preserving the fabric's quality and color. I personally like the feel of the shorts once they are machine dried: the fabric softens and the seams curl, creating the classic ripple.

I almost decided to wash and dry every pair before getting them ready to ship. That way, when customers received them, they would already have a lived-in feel. This is a trick most brands use. They even go beyond the mechanical wear of basic wash and dry and use chemicals to break down and soften fabrics. The customers receive a garment that feels like a beloved item they’ve had in their closet forever. A new T-shirt has the same feel as a vintage one worn and washed hundreds of times because the softening process breaks down the fabric equivalent to hundreds of wears. The garment may feel great when you first receive it, but its longevity and quality have been stripped away to get that result. I decided not to prewash the shorts. I’d rather sell slightly stiffer garments and let them soften the old-fashioned way: normal wear of people actually wearing them.

THE PRICE

In the case of the shorts, I did not have scale on my side to reduce the cost. The farm acreage I invested in grew only enough cotton to make a sample amount of fabric, which doubled the weaving price. Mineral dyeing is a labor and time-intensive process of extracting and dyeing under the correct conditions. I made a relatively small quantity of the shorts, so the cut and sew prices were higher because they had to learn the construction and set up the factory for only a few hours of work. Also, Oshadi ensures everyone along the way earns a fair wage. In the end, the final price of the shorts cost me more to make than the retail price of my original nylon shorts.

The industry standard for clothing is that the retail price is at least five times the cost of goods. Three times is what is considered needed to keep the lights on. That means my original nylon shorts cost less than $10 to make. If 30% is material costs and 20% is shipping and import costs, then the people involved in extracting the oil, synthesizing it into nylon, operating the spinning and weaving machines, dyeing the fabric, sewing the seams, and packaging it made less than $5 combined. Even though all of these processes took place in countries with different wages and cost of living, $5 is remarkably low. Still, most consumers expect shorts to cost less than $50. Mine cost $135 and I’m taking a little less than a three times markup.

Along with the shorts, I made a pair of simple pull-on pants with the same material and similar fit.

Please leave a comment or like the post if you’ve enjoyed it, and check out the shorts, pants, merino baselayers, and sweaters on my brand’s website!

Really enjoyed reading about how you made these shorts, Mairin!

Love reading about your process, Mairin! Can’t wait to buy these when I’m a little more flush! 🤍