Almanacs are resources to understand how natural cycles interact with specific topics. Each month, The Mindful Designer’s Almanac offers musings about natural fibers harvested that month or season. In China, March is the start of the mulberry leaf harvest to start feeding silkworms.

Silk is known for its silkiness, a characteristic synonymous with many other words that start with S: smooth, shiny, soft, supple, slippery, etc. Although these characteristics are inherent to silk to some extent, achieving the silkiness we associate with silk is a careful practice of reducing friction, because what makes silk silky is a lack of friction.

Like all natural fiber textiles, creating silky silk starts at a farm. The domestic silkworm (bombyx mori), the most common insect to produce silk, exclusively eats leaves from the mulberry tree. The higher the quality of the mulberry leaves, the higher the quality of silk the silkworms reel for their cocoons. There are conventional approaches to increasing the size and quantity of leaves the trees produce, such as GMOs and synthetic pesticides, and more natural ones, such as composting and integrated pest management. In the end, the most important thing for silkiness is that the farm produces a high quantity of quality mulberry leaves for the larvae to eat.

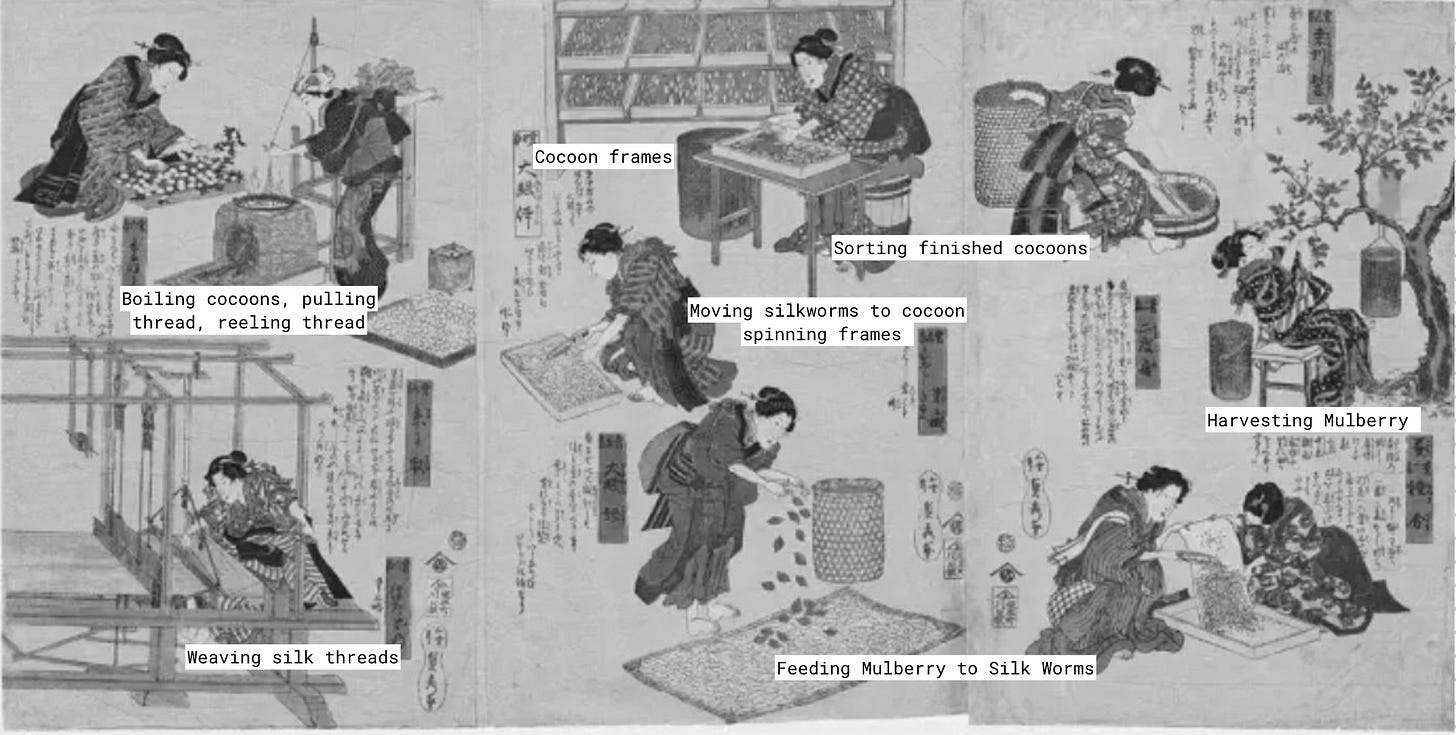

After the farm, the art of sericulture begins. Sericulturists carefully shepherd the larvae through each step of their development. The silkworms start on long tables covered in mulberry leaves. Once they are big enough to start making their cocoon, the sericulturists move them to special cocoon-spinning frames. They then sun-dry the frames and remove the finished cocoons. All of these steps require specific temperatures and humidities to achieve a long, fine, and consistent fiber. Once the cocoons are loose, the sericulturists sort them by quality. The highest quality cocoons are relatively large because they are surrounded by an extra long, continuous thread.

Spinning silk is unlike other natural fibers because it does not involve twisting together smaller fibers into one continuous thread. Instead, reeling silk involves extracting the already long thread from the cocoon and winding threads together onto a spindle. Each cocoon has about 1,000 meters of thread on it. To ensure the continuous thread does not break from the silkworms escaping, the spinners boil the cocoons in hot water, find the end of the threads, and attach them to the spindle.

A weaver then transforms the reeled silk into fabric. The silkiest silks are satins. Like twill, satin is the name of the weave structure. Weaving fabric is when you take vertical (warp) and horizontal (weft) yarns and place them over and under each other in a grid formation. A plain weave is when the weaver makes a perfect grid. A twill weave is when the weft goes under the warp three times before going over it once and repeating that pattern on a diagonal, creating the twill’s signature diagonal texture.

Each weave formation creates a different texture, and each time the warp goes under the weft and vice versa, the fabric gains friction. Satins overlap the warp and weft as little as possible on the fabric to reduce friction and increase silkiness. It does this by floating the warp over the weft. The weft yarn goes under the warp yarn four to eight times before it goes over the warp yarn once. The technique results in fabric with little friction because the weft interrupts the warp as little as possible.

Finishing processes further reduce friction for satin fabrics. A mechanical process called calendaring uses hot and pressurized rollers to smooth out any bumps and inconsistencies. Silicone Copolymers, a common chemical treatment for satins, chemically break down anything causing excess friction. Cationic softeners remove any ionic charges, which also reduces friction. The result of all these processes is silky silk.

Lower-quality silk cocoons or silk threads that break during reeling are made into silk noils. A fabric that more closely resembles cotton and is definitely not silky. Even high-quality silk threads can have different weave structures, finishes, and less silky hand feels, like silk organza or crepe. Cotton, rayons, polyester, and blends can be woven using satin weave structures to make silky fabric without silk. Just as canvas is named canvas because it was traditionally made with hemp (from the cannabis plant), silky does not necessarily mean made with silk. Even when made with silk, fabric is silky because of all the decisions farmers, sericulturists, spinners, weavers, and finishers made along the way.

Read last year’s post about silk

MARCH: SILK

In March, mulberry trees in the Pearl River Delta start producing leaves, and farmers begin the first of eight harvests from March to December. The leaves go to special silkworm-rearing sheds nearby, where silkworm larvae continuously eat mulberry leaves for around forty days before they gain enough energy to metamorphose into moths. They start by windi…

NOTES

https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2023/26/e3sconf_uesf2023_03088.pdf

https://www.safic-alcan.com/en/de/textile-enhancers-how-impart-silkiness-and-softness-your-textiles

https://cottonworks.com/en/topics/sourcing-manufacturing/finishing/chemical-finishing/#:~:text=Cationic%20Softeners%20This%20type%20of%20softener%20produces,and%20are%20compatible%20with%20most%20resin%20finishes.

So much good and interesting information! Thank you!