What Makes a Great Sweater Great

What producing sweaters for brands has taught me about shopping for sweaters.

Last month, I wrote about recreating one of my mom’s hand-knit sweaters for my brand, Mairin. The result is a rolled neck sweater, made with 100% High Andean wool, and hand-knit in Peru. I have a good handle on raw material quality, but I am no knitwear design expert. I played it safe making a simple design I knew I loved with the most basic stitch and no complex details. I also differed to the knitters in helping perfect the fit and deciding the technical details.

I believe in the fit and quality of my sweater. That said, knitwear is an art form that takes a lifetime to perfect, so the first sweater I created for my brand is not perfect, and neither are the vast majority of sweaters on the market. In most cases, sweaters are no longer the heirloom pieces they once were; the supply and demand for sweaters have skyrocketed in the last two decades. Sweaters have shifted from investment pieces to another category in fashion’s ever-increasing cycle of overproduction.

Good-quality sweaters still exist! They just take some know-how to find. Inspired by developing a new sweater for next fall, my conversation last month with Hadley Hammer from TOGS, and increased discussions about sweaters and quality on Substack, I am doing a deep dive into what makes a sweater great.

This guide is based on my experience producing sweaters for other brands and my own, visiting with and learning from knitters and fiber producers around the world, and a personal love for really great sweaters. This post will cut off in email, so read on your browser or app for the entire guide. It will cover:

What materials are the best quality

Knitting techniques and which materials are better suited for which stitches

Sweater design and fit

Proper sweater care

A list of recommended brands

MATERIALS

When it comes to materials, sweaters should be 100% natural fibers, ideally animal fibers. Wearing animal fibers is so cool– it's the only clothing material where the function of the garment perfectly mirrors the material's function in nature. Sheep, goats, alpacas, and yaks grow fiber to keep them comfortable and protect them from the elements, which is the same reason we wear sweaters. There’s no innovation needed, nature already took care of it.

Natural animal fibers age and change over time, which many argue gives synthetic materials a competitive edge in terms of quality. But polyester sweaters do not change and age (i.e. decompose) just during the time someone actively wears the sweater but also for the 1,000+ years after they are done wearing it, and that argument usually comes from brands that are paying a fraction of the price for acrylic yarns versus natural ones. With proper care (more on this below), natural animal fibers can maintain their quality just as well as synthetics and have the added benefits of the fiber’s natural properties.

I will focus on the main animal fibers on the market: wool, cashmere, and alpaca. Many different types of sheep, alpacas, and goats produce fiber, each with their distinct fiber quality. To overly simplify things, longer and finer fibers are higher quality across the board. Short fiber will fray quickly which causes piling. Thicker fibers are less flexible and more abrasive which causes itching. Different breeds produce different qualities of fiber: Merino sheep produce the finest wool, Suri alpaca produce the finest alpaca, and pashmina goats produce the finest cashmere.

Regardless of breed, each unique animal produces its own specific quality. Not all Merino sheep produce the same fine, strong fiber, for example. Breeding animals for fiber is a complex science and fiber quality is dependent on genetics of the herd, quality of life, and diet. Even within a herd, each animal will produce its own quality of fleece.

To zoom in further, each animal has a different quality of fiber on different parts of their body. Alpaca and sheep grow the finest fiber on their sides and shoulders, while their legs and backs are coarse. Alpaca fleece from one animal is categorized into seven categories: the finest fiber only found on some alpaca’s chest is called royal alpaca, the next best is baby alpaca (not from actual baby alpacas, fiber from adult alpacas' backs and sides), then superfine alpaca is the middle of the road, then the coarser varieties. Wool and cashmere are similarly categorized after shearing.

How do you know what quality of fiber a sweater is made from when shopping? The answer is it is really hard to know. Most brands don’t talk about their fiber quality. Most designers focus on the look and feel of a fiber once it's knitted, not its specific fiber quality. Also, materials are usually the most expensive cost of a sweater. Often designers have to choose to lower the fiber quality, blend it with polyester or cotton, reduce knitting density, or take out complex stitches to hit certain price points.

I find the only time a brand talks about fiber quality is when they spend the money on more expensive fibers, but that still doesn’t necessarily mean the sweaters are high quality. The best way to discern the material quality of a sweater is to wear it a ton and see how it performs over time. Before buying it, the best way to see that is through customer reviews and testimonials about a sweater, like Out of the Bag’s post about Babaà sweaters:

KNITTING

A sweater is a full fashion knit, which means the entire garment is knitted, with no sewing involved. There are three main ways to knit— hand-knit, handloom, and machine. In hand-knitting, someone physically knits the garment with needles. A handloom is a machine that someone hand operates. Machine knitting is a hands-off process where a powered machine does all the work.

Which technique is better depends on the design, yarn, and thickness. A chunky sweater with novelty stitching is best for hand-knit. A sweater with simpler stitching that's intended to have a handmade look is best for handloom. Thin sweaters or sweaters with high tension are better for machine knitting.

A knitting machine in Arequipa, Peru knitting a cardigan sleeve with a pointelle stitch.

Most sweaters on the market are machine knit, it's cheaper, quicker, and more consistent than handloom and way cheaper, quicker, and more consistent than hand-knit. Although machine sweaters are perfectly fine, you lose that certain heirloom, handmade aspect of a hand-knit or loomed sweater. For all three knitting techniques, the quality of the knitting comes down to the operator, the quality standards of the knitting factory or company, and how well the design, knit structure, and material choice go together.

DESIGN

Design is the most important aspect of a sweater’s wearability. You can have a beautiful hand-knit sweater made with the highest quality yarn, but if it doesn’t fall on the body right, you probably won’t wear it.

I talked to my friend and freelance knitwear designer, Amanda Chudacoff, and she explained knitwear design to me better than I ever could:

Knitwear design is different from other design categories because it combines textile design and apparel design. As opposed to wovens or cut and sew knits, with fully fashioned knitwear, you are designing the fabric structure while you design the garment. It's one of the more technical design categories— one change to the knit structure (tension, stitch, width, etc) can affect the whole garment.

Knitwear design is the combination of so many tiny decisions and one wrong one can ruin a sweater. For example, if a designer chooses too heavy of a yarn or too dense of a knit for a chunky, oversized sweater, the weight of the material will cause the sweater to grow. It may fit great the first time you put it on, but as you wear it, the sleeves grow longer, the width increases, and the stitches at the shoulders start opening up. This is usually the case when designs are inspired by wool garments but made with alpaca, cashmere, or blends. Wool has much more elasticity or memory than other fibers, so chunky wool sweaters bounce back to the original design during and after wear.

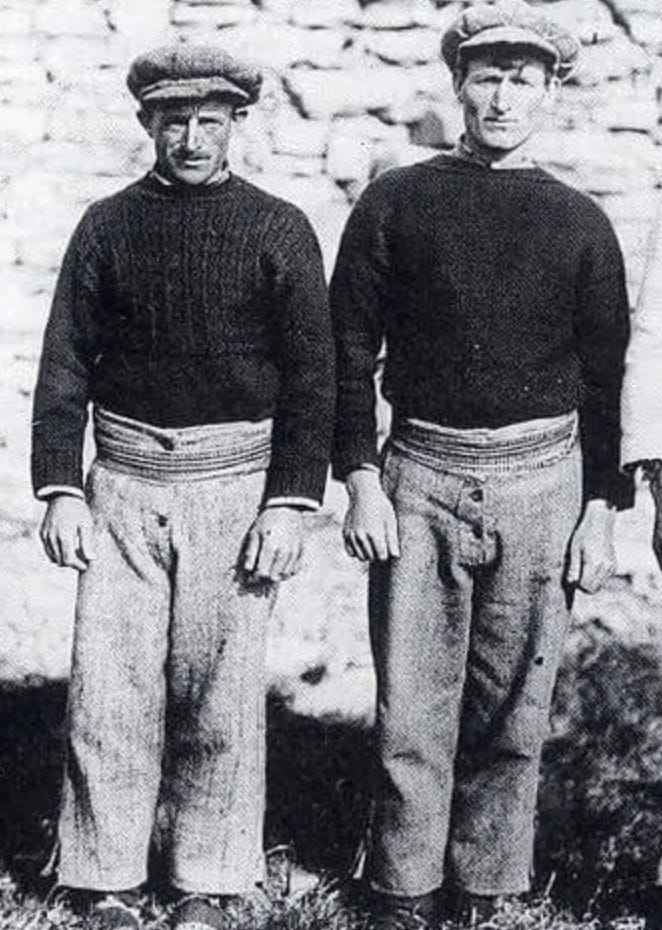

Luckily most sweater designs on the market are iterations of, or inspired by, traditional sweaters. For example, fisherman sweaters originated in Ireland where short and fine lambswool was readily available and hand-knit into the thick sweaters with intricate stitching. For the sweater I released this fall, I wanted it to be a substantial layer that is thick and keeps its shape. I wanted the feel and wear of a classic fishermen sweater, even though I did not use any of the novelty stitches. So I chose to use 100% wool from the High Andes where the sheep variety is similar to those in Ireland and have the sweater hand-knit.

Peruvian knitters traditionally knit fine alpaca in tight stitches, often changing the stitch or colors every row, making intarsia-like patterns. The resulting sweaters drape and hug the body more than a wool version. Next fall, I am making a layer that I want to be lighter-weight but still warm that my customers can wear as a mid-layer over the Merino baselayers and under the wool sweater. I decided to use alpaca and machine knit this one, so the knit structure can be super tight and the sweater can drape nicely.

A knitter in rural Peru hand-knitting a traditional hat. Source.

Although having a basic understanding of what makes a sweater good quality is helpful, the most important thing about the design of a sweater is that you like the fit, look, and how it feels on your body. The best sweater designs are the ones you wear over and over again.

CARE

Heat and friction are animal fiber’s worst enemies. Animal fibers are covered in tiny scales which makes them thermoregulating and water resistant, but the scales will curl with friction and heat. This causes sweaters to pill, shrink, and felt. Correct care is crucial to keeping a high-quality sweater, high-quality.

One of the many benefits of animal fiber is that it naturally traps and then releases odor and dirt. Sweaters do not have to be washed often. I wash the sweaters I wear all fall, winter, and spring about once a year or less. This is how I do it:

Soak the sweater in cold water with wool detergent. I use Eucalan, it’s the best

Lightly swirl the sweater around to remove any excess dirt or grime

Rinse the sweater until the water is clear

Hold the sweater over the sink to drip out excess water

Lay the sweater flat on a towel and reshape it

Roll up a towel and put it in a warm place

Leave for a day or two

Replace the towel, reshape, and roll again

Once almost dry, I hang the sweater for a day to release any extra moisture

Once dry, I give the sweater a good combing

RECOMMENDATIONS

Although I spend a lot of time thinking about clothing, I actually don’t shop much or own a ton of clothing. If you can believe it from this guide, I tend to overthink purchases to the point that I just avoid them. But I have a few recommendations from my own closet and my wishlist. When I shop for sweaters, I first look at brands or designers that focus on knitwear. They are probably going to have a better handle on quality knitwear design than those working in a bunch of categories.

Mairin: I am biased with this one because it's from my brand, but I think it is a great piece. The yarn is super soft, the design is simple, and it’s hand-knit.

Lauren Manoogian: I don’t own any of her sweaters, but I have heard about her process. She truly understands knitwear and works closely with the yarn mills and knitters to create unique, quality designs. Her sweaters are not cheap but they are worth the cost— true investment pieces.

Wol Hide: Like Lauren Manoogian, the designer behind Wol Hide really cares about the textiles in her pieces and creates beautiful combinations of stitches, materials, and designs. She’s also often the first brand to use regenerative or climate-beneficial materials.

James Steet Co: I have the Lowe sweater in two colors and love the fit. You can tell it was designed by a knitwear designer and it’s made with my favorite stitch: the half cardigan. It’s an alpaca, wool, and nylon blend and does fall into the trap of growing as you wear it because it's so oversized. I have not been impressed by the material quality of the other sweaters I’ve purchased from James Street Co.

Babaá: I don’t own any Babaá but feel like I do because there are so many extensive customer reviews, blogs, and posts about them. Most people love them, but some note itchiness and the stitches being too loose. It’s cool that their supply chain is all in their home country, Spain (where Merino wool originates), and they are committed to rereleasing a few great styles every year.

Secondhand: Sweaters aren’t made like they used to be—the average quality of a sweater was so much higher than it is now. The only downsides is that a lot of used sweaters were not maintained correctly— they’re felted, shrunken, misshapen, or have moth damage.

Please comment any sweaters you love or brands you recommend avoiding. I hope you enjoyed this guide and let me know in the comments if you have any sweater questions, too.

Here are previous Mindful Designer’s Almanac posts that go more into the impact and sustainability of different animal fibers.

APRIL: MONGOLIAN CASHMERE

In April, the days in Mongolia start getting warmer. Before the days get too warm and their animals voluntarily shed their winter coat, Mongolian herders corral their goats and comb out their undercoats. Cashmere goats have a coarser overcoat that protects them year-round and a fine undercoat that they grow in the fall to protect them from the long, col…

As a sweater lover and knitter, I really enjoyed this piece! My favorite sweater is a cashmere Brora cardigan I purchased on eBay almost a decade ago. I hand wash my wool sweaters and it’s beautifully soft a fuzzy without pilling. My only complaint is that it is seamed with thread rather than the same yarn it is knit with, as it has developed a small moth hole and I would have liked to use that yarn to mend it invisibly.

An informative and nicely documented piece. I tend to avoid wool due to the environmental degradation and animal and human exploitation perpetrated to harvest and produce animal-derived materials and skins, so my preferred choices are usually 1) Vintage hand-knitted sweaters, 2) New knits in 100% cotton, 3) New knits in 100% recycled wool. Rifò is an Italian company with a strong focus on recycled wool, and despite not owing any of their sweaters, I found their material choice so appealing. Is recycled wool a thing also in Peru and/or South America?