I produce merino wool baselayers that never leave US soil for my clothing brand. The wool comes from a collective of Oregon, California, Nevada, and Colorado ranches, whose harvest goes to North and South Carolina for cleaning and spinning, Massachusetts for knitting, and Los Angeles for cut and sew. I chose this supply chain because it ticked all the boxes for me. The fabric aligns with my mission— the ranches use regenerative practices, and the mills use little chemical and mechanical intervention to produce the yarn and fabric. Also, the fabric has no minimums, so as a new brand with little capital, I could order a very conservative quantity for my first collections.

Before finding this option, I spent months researching import suppliers, each one had either extremely high prices, a non-traceable supply chain, or unrealistic minimums. It felt too good to be true when I remembered a conversation with a rancher in Oregon that I had a few years prior. She spent over two decades building a US supply chain for the wool harvested from her ranch. One of her points of pride was that her ranch and the ranches in the collective she created grew such fine, durable wool that they could produce extremely lightweight baselayer fabric. A perfect match for the styles I wanted to make.

The sampling process went quickly once I found this fabric. Production did not go as smoothly. The yarn shipment to the knitting mill was late, making my production two months later than I planned. Lightweight knit fabrics, especially wool, curl on the edges, making the sewing take longer than we expected. Finally, in high summer, I received my first collection of merino basics. The worst time to sell products associated with cold-weather layering. But they did surprisingly well, and I sold out of most sizes and colors by September. So I placed another fabric order, and this time, the fabric shipped immediately, just in time for a mid-fall release, which sold out even faster. So I placed another order, planning to restock around the holidays. That fabric order just shipped this week, seven months late.

About 3% of clothing sold in the US is made in the US, which means sewn in the US. The majority of fabric and other inputs are imported. Most textile mills in the US share the same primary customer: the military. The military must wear clothing grown or extracted and produced on US soil, with some exceptions for specialized materials that the US manufacturing base cannot produce. The multi-million-dollar military contracts are what keep US textile mills afloat and a small community of skilled workers employed. As a private brand, it is not the norm to work with domestic mills, unless they happen to have the exact fabric the brand is looking for at a competitive price or that is a part of the brand’s mission.

During the past seven months that I’ve been in limbo on my fabric delivery, I looked into other options. There are a handful of small, hip running brands that have popped up in the past few years. They offer baselayers with Japanese wool. So I did some digging, and they are most likely getting the wool from a mill in Wakayama, Japan. It is not “Japanese wool” in that the wool is not grown in Japan. Just like US-made clothing is often made with imported fabrics, this popular wool fabric supplier imports yarn from China, spun with wool fiber from South African sheep. Their minimums for bulk pricing are 300 yards, which is reasonable, and they ship within two months. I was intrigued. Although the supply chain was not as straightforward as I had hoped, I liked the lead time, and I loved the swatches they sent. The only problem, the swatches didn’t feel like wool; they felt more like a blend. So I asked about the chemical treatments of the yarn and fabric, and learned they treat both with toxic and non-biodegradable finishers to give the fabric a better hand and make it easier to wash. Although this supply chain had the potential to be way less stressful and more predictable than my current domestic one, it had too many red flags to align with my brand’s mission.

I’m back to square one. I’m talking to other domestic mills, so I have options if my current mill’s machine goes caput again. They’re all optimistic they can make the fabric, but none have successfully tried yet. If I have learned anything in the last seven months, it is all the ways circular knitting wool in the US can go wrong. The yarn can break and need to be sent back to the spinning mill for re-waxing, the one machine that knits this quality can stop working, the only mechanic in the country who can fix it can be on vacation, or the only technician who operates the machine can go on personal leave.

No matter if you are producing clothing in the US or abroad, there are bound to be bumps along the way. But in a country like the US, where there is such a small textile manufacturing base, little access to skilled workers, and few machines, it is nearly impossible to quickly pivot when things go wrong. You lose the predictability you would get importing from countries with more turn-key supply chains.

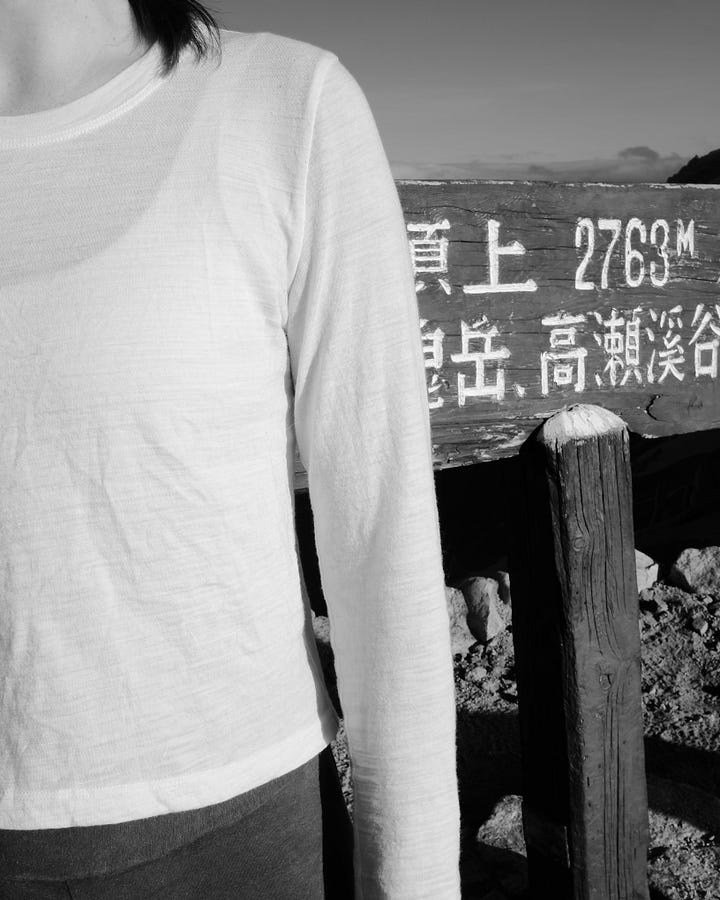

I love using wool from the American West for my baselayers because most of my customers live in the West and wear these layers exploring the same climates and ecosystems the sheep roam. They get to wear clothing perfectly adapted to those mountains. It seems simple to use wool that our neighbors grow and process it at mills that our taxes help keep open. But clothing is reliant on convoluted global supply chains. It is a lot cheaper, easier, quicker, and more consistent to grow wool in South Africa, spin it in China, knit it in Japan, and sew it in LA than to grow and produce it domestically. And, it will take a lot more government commitment and investment in US textile manufacturing than tariffs to change that.

I will be starting a pre-order for the merino baselayer in a couple of weeks. The mill was only able to produce a small amount of fabric, so I think they’ll sell out fast. Sign up for the mailing list here to be notified when the pre-order is open!

Thank you for sharing this process! Your dedication to you values is inspiring. Learning that most US textile manufacturing relies on the military is... depressing to say the least, but not surprising.

This is fascinating, thank you! I didn’t know that about military clothing rules