SEPTEMEBER: HEMP

THE PLANT

In mid-September, tens of thousands of hectares of industrial hemp are ready to harvest in Heilongjiang, China- the world’s largest producer of hemp for fiber. Small, rural farms in these northern reaches of China set aside hectares every April for their most profitable and beneficial crop. After a short growing season, the mature hemp towers over two meters tall with ample leaves and seeds.

Hemp is the epitome of a multipurpose crop (Figure 1). Every part of the mature plant can be sold for different uses- the stalks for fiber, seeds for food and oil, and leaves for pharmaceuticals. But, the full benefit of growing hemp goes beyond the monetary profit of its co-products and starts long before the harvest.

Figure 1: Flow chart of hemp’s many co-products.

Much of hemp’s advantages are due to its roots, which grow up to a meter long. The roots aerate, introduce organic matter, and build aggregates deep in the soil- increasing micro-biodiversity, improving access to nutrients, and reducing erosion to soil layers left untouched by most crops (Figure 2). Hemp’s deep roots also capture and process heavy metals, petroleum, pesticide build-up, and other harmful chemicals, cleaning and restoring the contaminated soil.

Figure 2: Hemp farmers in Heilongjiang chopping the mature stalks, leaving their roots to decompose and continue to benefit the soil below.

Hemp continues to regenerate its surroundings above ground. Able to quickly grow in dense patches, hemp outcompetes weeds, eliminating the need for herbicides and suppressing weeds for the next crop in rotation. Hemp also attracts pollinators, is naturally pest-resistant, needs minimal water, and grows in a wide range of climates and geographies.

Hemp has amazing potential in both the tangible products and its auxiliary benefits to the environment. However, hemp clothing is only sold by small brands or large brands’ special projects. It makes up less than 0.2% of fiber used for textiles.

A NEW ERA IN HEMP

Cotton is king. It is ubiquitous and far outcompetes any other natural fiber. Its success is thanks to more than its potential as a product. Cotton had and continues to have a perfect combination of factors, including investment, innovation, slavery, and subsidies.

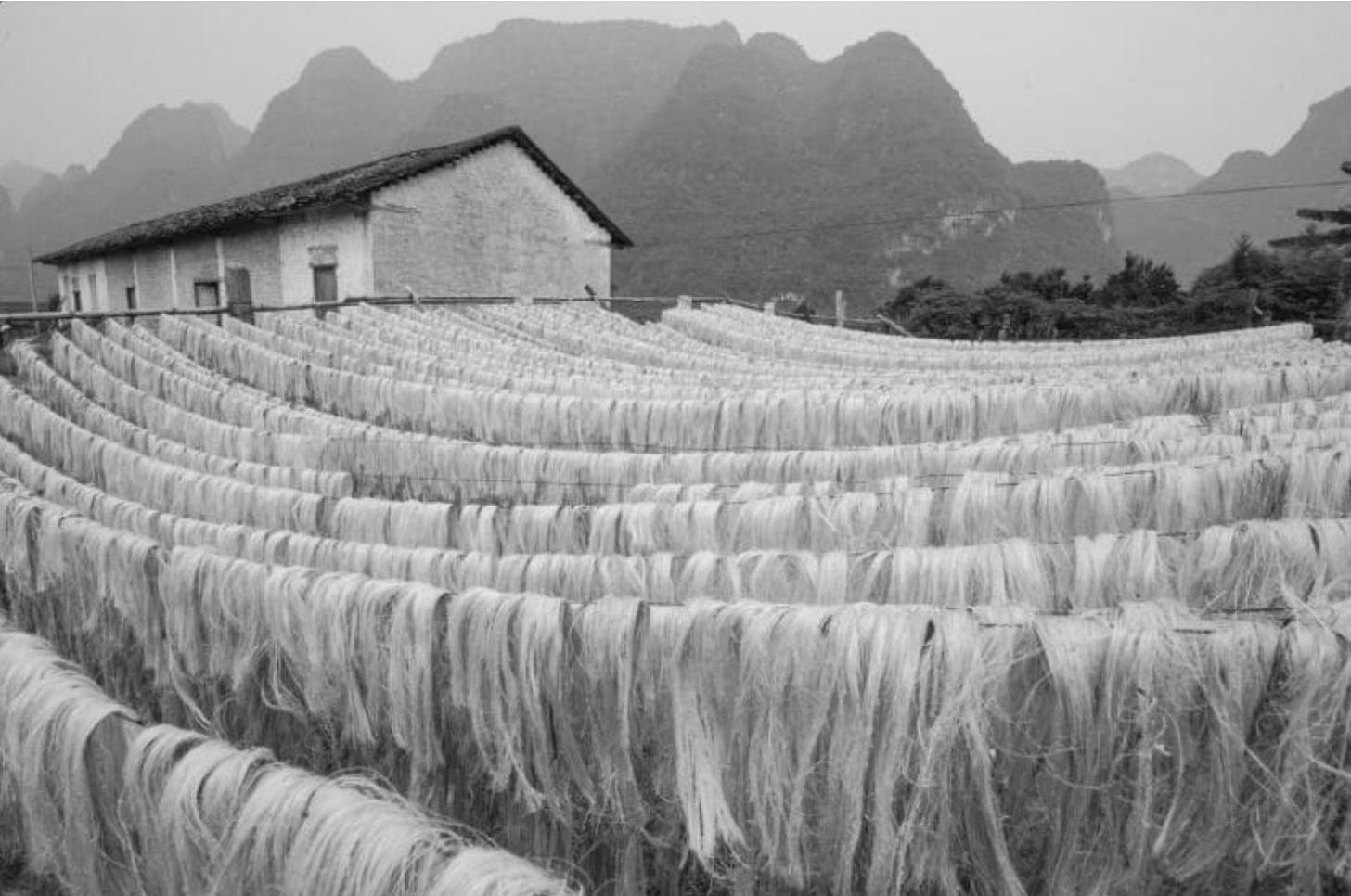

Hemp’s journey has been the opposite of cotton’s. The same governments that supported cotton farmers with generous subsidies banned the production of industrial hemp due to its association with marijuana. Then came a divestment in hemp processing, which to this day is still labor-intensive from farm to finished goods (Figure 3). These and other economic and political forces suppressed hemp’s ability to grow as a global commodity and major textile input, but that may soon change.

Figure 3: The labor-intensive process used by many Chinese farmers of manually drying hemp fiber on lines after retting and removing the woody parts of the stalks.

Chinese cotton is losing traction. In the 1950s, China set up military-run cotton farms in Xinjiang. By 2017, 90% of China’s cotton came from them. But there was a problem- researchers were finding evidence of forced labor on these farms. The Chinese government detained Uyghurs, a Turkic, Muslim ethnic group, without legal justification and forced them to hand-harvest cotton and work in yarn and textile factories. As of 2020, one in five cotton garments in the market was tainted with forced Uyghur labor.

After four years of brands and governments claiming a lack of evidence, a 400-page Chinese government document leaked. It proved the systematic detention of and state-sponsored human rights abuses against the Uyghurs. Brands started pledging to not knowingly buy cotton products from Xinjiang and the United States enforced import bans on Xinjiang cotton and goods.

Catalyzed by the global divestment from Xinjiang cotton, Chinese cotton production decreased for the first time this century. As China scrambles to fill the gap and continue to lead the world’s textile and clothing industry, it looks to new inputs. Strategies include importing more raw cotton and yarn, using up its cotton reserves, and investing in new fiber sources, including hemp.

In 2010, the Chinese government lifted its 35-year ban on growing hemp. Then it endorsed and heavily invested in the hemp textile industry because of its potential contribution to an "ecological civilization.”

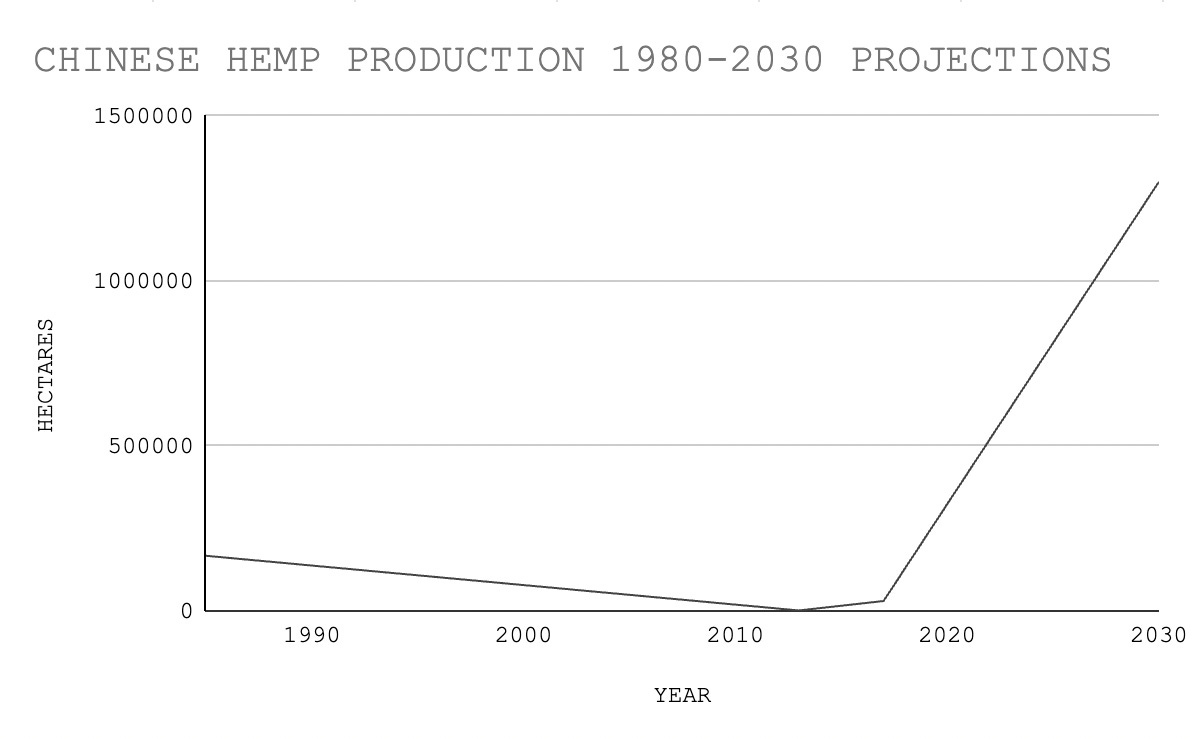

Heilongjiang, China is the current center of hemp’s rise. From 2013 to 2017 hemp cultivation in Heilongjiang increased from 1,300 ha to over 30,000 ha. The cultivated area continues to skyrocket, all part of China’s plan to grow hemp on 1.3 million ha by 2030 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Hemp cultivation over 50 years based on estimates.

Although hemp is considered a sustainable textile, that could change as it moves away from its fringe status. China’s plan to increase cultivation by 100,000% over 20 years is a lofty goal that may require cutting corners. As hemp becomes a bigger player in the global market, it has the potential to lead the industry in a positive direction, become just as exploitive and extractive as other major global commodities, or land somewhere in the middle (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Questioning how hemp will grow as a commodity.

NOTES

https://textileexchange.org/app/uploads/2023/04/Growing-Hemp-for-the-Future-1.pdf

https://sewport.com/fabrics-directory/hemp-fabric

https://www.peertechzpublications.com/articles/IJASFT-6-180.php

https://hemptoday.net/the-chinese-strategy-planning-a-roadmap-to-hemps-future/

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hemp-china-new-big-normal-tim-jablonski/

https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/41740/15855_ages001ee_1_.pdf?v=0

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0926669014003987

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

https://enduyghurforcedlabour.org/