Cheap Cotton, Expensive Subsidies

How farmers in Texas can make millions growing cotton for $5 T-shirts sold in Walmart.

Almanacs are resources to understand how natural cycles interact with specific topics. Each month, The Mindful Designer’s Almanac offers musings about natural fibers harvested that month or season.

In October 2022, cotton farmers in Texas had fields full of scorched and shriveled cotton plants. Their large machine harvesters picked and baled what they could, the rest of the fields were left unharvested. The drought year forced farmers to walk away from 60-70% of acres they planted with cotton.

Texas farmers dryland farmed more acres than they have in recent history, because their main water source, the Ogallala Aquifer is depleted. Cotton is a great dryland crop and US breeders have created drought-resistant varieties that maintain fiber quality and length. However, these new varieties were not resilient to the record-breaking drought. Areas of West Texas, which receive an average of 10 inches of precipitation, only got 0.5 inches of rain in 2022.

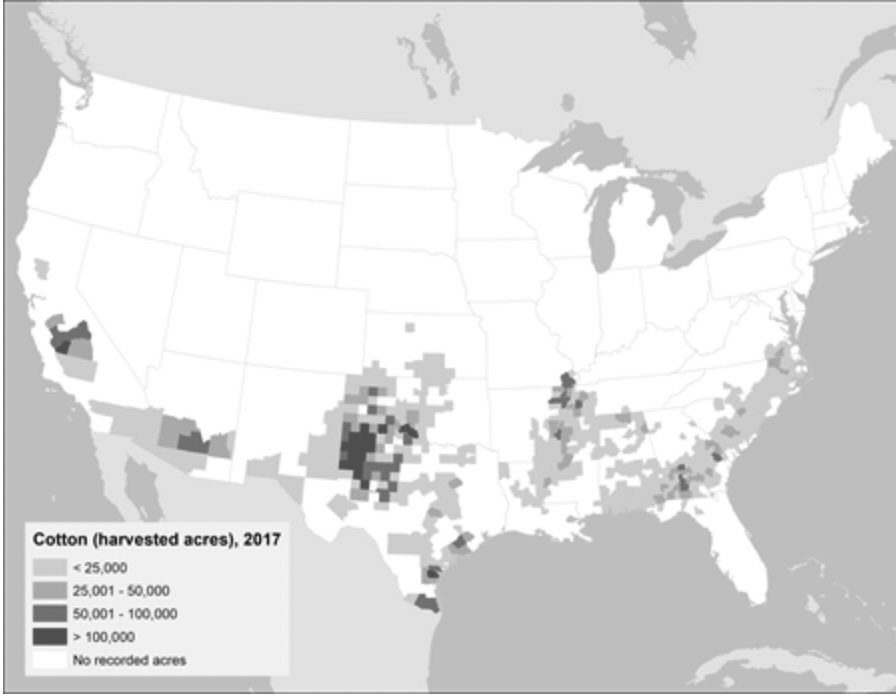

The US is the third largest producer of cotton, and Texas produces around 40% of it. The drought in 2022 had huge implications for the global cotton market: Texas cotton makes up around 5% of the market and the drought in 2022 caused a loss of 2 billion dollars worth of raw cotton.

Despite this hit to the global cotton supply, the price of cotton actually decreased in the fall of 2022, the global cotton stock was at its highest, the largest cotton farmers in West Texas had a highly profitable year, and the consumer price of cotton clothing did not increase.

DISTORTED MARKET

Worldwide 110 million households are involved in growing cotton. Some are small-holder farmers in West Africa making less than $1.00 a day and some are multi-millionaire farmers in West Texas. They sell cotton to the same global markets for the same price– most likely to China for spinning and weaving, then Vietnam or Bangladesh for sewing, and then shipped back to US retailers to be sold for prices that seem impossibly low.

That’s because the prices are impossibly low. The price of raw cotton does not account for the actual cost of growing cotton. Especially in Texas where farmers plant expensive seeds (BASF’s Agricultural Solutions, which produced the drought-resistant seed for Texas farmers, has an annual revenue of $8.4 billion), irrigate with expensive water, control pests and weeds with expensive chemicals, and harvest the cotton with expensive machines (a John Deere cotton picker costs $960,000 and comes with touchscreen controls and a/c). Cotton farmers in the US make half or more of their revenue from taxpayers' dollars in the form of subsidies.

The cotton that approximately seven thousand farmers in the US grow is so uncompetitive in the world market that subsidies are the only way for it to be an economically viable crop. Cotton, along with corn, soybeans, wheat, and rice, are called the Big Five because US farmers growing these crops receive a disproportionate amount of subsidies. The subsidies include direct payment to farmers, border protections, insurance, support with inputs, help with marketing, and minimum prices. In 2022, the US government paid $6.8 billion to Texas cotton farmers in crop insurance alone. Farmers were also able to receive payouts to match minimum price guarantees for the cotton they were able to harvest and sell.

American reliance on subsidies means that the state has a huge influence on land use, farming practices, prices, and resource distribution. Farmers choose to grow cotton not based on the market price or availability of inputs, such as water, but because it is one of the most supported crops by the US government subsidies.

These subsidies have a ripple effect on the millions of other farmers who rely on cotton for their livelihood worldwide, especially on farmers in countries without funds to offset the distorted market. Most years the amount of subsidies the US pays cotton farmers is equal to or more than the entire GDP of Benin, the ninth largest producer of cotton. A 2007 Oxfam report found that reforming the US cotton subsidies would lead to increased West African cotton farmer income to feed an additional million children or pay school fees for two million children.

In 2002, Brazil brought a trade dispute to the World Trade Organization against the US. Brazil argued that US subsidies on cotton violated trade commitments by creating unfair competition and depressing prices for Brazilian farmers. Brazil won. As part of the settlement, the US paid Brazil $750 million for their losses and agreed to reform cotton subsidies in the 2014 farm bill. The 2014 farm bill did away with direct and counter-cyclical payments. With a strong cotton lobby, farmers are still able to get many of the pre-2014 benefits through a complex system of programs. Many of which Texas farmers dipped into in 2022, so that the devastation of their crops did not lead to the devastation of their finances.

The unequal distribution of support to cotton farmers globally is most poignant when comparing Texas’s 2022 drought to the 2005 drought in India (or any drought in the last 20 years in India). Since the introduction of GMO cotton seeds in India, farmers are more indebted to seed and chemical companies than ever before. A debt cycle that leads cotton farmers to feel hopeless in years when their crops fail, such as the drought year in 2005 when hundreds of Indian cotton farmers committed suicide by drinking pesticides.

The United States is not the only culprit of the state manipulating cotton’s supply and demand balance. Eleven cotton-growing countries provide some level of state support. China is the second-largest producer of cotton and the largest subsidizer of cotton, around $40 billion per year. China’s main cotton-producing region, Xinjiang, is home to government-owned and operated farmers supported by government-sponsored forced labor. Also, China is the world’s leader in cotton manufacturing and has the world’s largest reserve of cotton. When annual imports dip, China sells its manufacturers cotton from the reserves to keep prices down. All of this manipulates the price of cotton and augments the divide between those profiting from and those paying the price of keeping cotton cheap.

Ideally, subsidies benefit all farmers and the people who eat or wear their harvests– increasing crop security, creating consistent pricing, and providing resources to improve farming. But with lobbies and other interests, subsidies support cycles of dominance and exploitation. Just as subsidized corn, soy, wheat, and rice feed the overproduction of cheap, low-nutrition foods, subsidized cotton feeds the overproduction of cheap, low-value clothing. The largest farms growing monocropped, Big Five crops with GMO seeds and heavy chemical inputs benefit the most– in 2019, the richest 1% of US farms received one-fourth of total subsidies. Ultimately, our tax money supports the race to the bottom to grow a surplus of $5 cotton T-shirts for retailers like Walmart rather than invest in farming techniques to improve our soils, climates, and health.

NOTES

https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/cotton.pdf

https://downloads.usda.library.cornell.edu/usda-esmis/files/kp78gg36g/h415qk15b/7h14bz79m/cotton.pdf

https://fas.usda.gov/data/cotton-world-markets-and-trade-09122024

https://oxfam-us.s3.amazonaws.com/www/static/media/files/paying-the-price.pdf

https://kingpinsshow.com/cotton-subsidies/

https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/cotton-and-wool/cotton-sector-at-a-glance/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959378024000487

https://books.google.com/books/about/Empire_of_Cotton.html?id=1QzhngEACAAJ

https://www.ewg.org/interactive-maps/2021-farm-subsidies-ballooned-under-trump/

I feel as though liking this post isn’t quite the right thing to do, but I appreciate the reminder!

Thanks for putting this together!